Key takeaways from the article

Emerging fund managers are typically those launching small or first-time funds with limited track record but substantial prior professional experience in investing.

They differ from established funds by operating with smaller teams, offering greater strategic flexibility, making faster decisions.

Limited partners allocate to emerging managers seeking outperformance potential, better alignment of interests, and exposure to underrepresented strategies or markets.

Key risks include execution risk, key person risk, weaker operational infrastructure, and higher regulatory scrutiny, yet these can be mitigated.

Evaluation focuses heavily on team pedigree, investment discipline, repeatable fund strategy, and qualitative factors over short-term performance metrics.

Emerging managers contribute to portfolio construction by increasing diversification and accessing higher-performing opportunities with greater dispersion.

Successful investment in emerging managers requires rigorous due diligence, ongoing monitoring, and acceptance of elevated early-stage uncertainty.

Who are emerging fund managers?

Emerging fund managers are investment professionals or teams raising their initial or early funds — usually under $500 million in size — with a short or non-existent institutional track record as general partners, though often backed by years of relevant experience as investment professionals. They operate across private equity, venture capital, and hedge funds, frequently targeting specialized fund strategies.

What is an emerging manager?

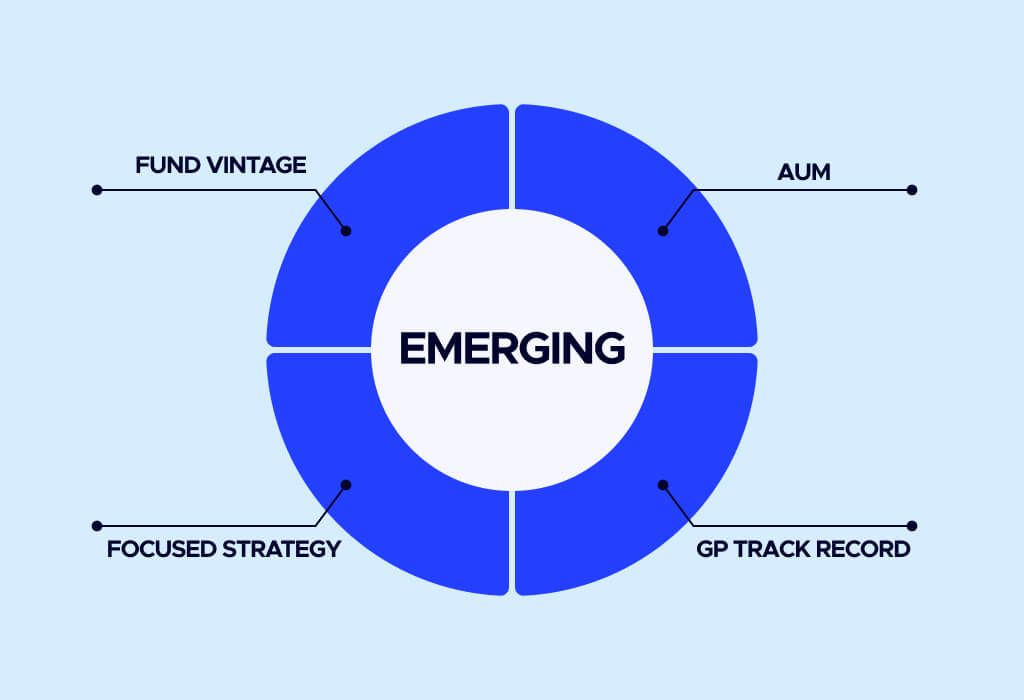

The definition of an emerging manager centers on funds and teams in the first or second vintage, characterized by modest assets under management, limited historical fund-level performance data, and a focused investment mandate. Typical criteria include:

First-time funds or funds with one prior vintage

Personal track record from previous roles at established firms, but no or minimal institutional-level results

Niche or differentiated fund strategy — sector, geography, stage or thematic focus

The label “emerging” refers strictly to fund-level maturity and scale, not to professional competence or capability. Many emerging investment managers bring deep domain expertise, prior successful deal execution, and strong networks from senior positions at blue-chip firms, distinguishing them clearly from inexperienced entrants.

How emerging managers differ from established funds

Emerging fund managers usually run leaner organizations with smaller investment and operations teams — often 5–15 people total — compared with dozens or hundreds at established platforms. This structure enables greater flexibility in investment strategy, allowing rapid pivots or opportunistic moves that larger funds with rigid mandates cannot pursue.

Deal sourcing often relies on personal networks and specialized knowledge rather than broad brand recognition, frequently providing access to proprietary or off-market opportunities in underserved segments. Decision-making is markedly faster due to fewer approval layers.

However, resource constraints are evident: limited internal operations, reliance on outsourced service providers, less sophisticated reporting systems, and fewer dedicated risk or compliance staff. These differences shape both advantages and vulnerabilities relative to established general partners.

Why investors care about emerging managers

Limited partners — particularly institutional investors — allocate to emerging managers because historical data across vintages shows meaningful outperformance potential. Smaller funds often benefit from better entry multiples, nimble execution, and alignment with high-conviction ideas.

Alignment of interests is typically stronger: general partners commit higher percentages of personal capital, carry structures favor long-term performance, and fees are sometimes more investor-friendly in early vintages.

Access to novel fund strategies, emerging sectors, new geographies, or underrepresented asset classes adds diversification value in portfolio construction. Including emerging managers helps limited partners capture alpha from less efficient market segments while spreading exposure across vintage years and manager profiles.

Key risks when investing in emerging fund managers

Primary risks encompass execution risk — the challenge of translating prior individual success into consistent fund-level results — and key person risk, where performance hinges heavily on one or two individuals.

Operational infrastructure is often underdeveloped, leading to wider institutional control gaps, weaker internal controls, and greater reliance on third-party administrators. Regulatory and compliance frameworks may be less mature, increasing scrutiny or operational friction.

These risks do not automatically disqualify an investment. When offset by strong team pedigree, disciplined processes, transparent governance, and realistic capital allocation expectations, many limited partners conclude that the asymmetry of potential returns justifies measured exposure.

How investors evaluate emerging fund managers

Assessment begins with a deep scrutiny of the team’s prior professional experience, deal track record, investment judgment, and ability to work cohesively. Investors probe the repeatability of the proposed fund strategy — whether the edge is structural or situational.

Investment discipline is evaluated through consistency of criteria, sourcing rigor, portfolio construction logic, and exit discipline demonstrated in past roles. Operational infrastructure, governance structures, valuation policies, and conflict management receive close attention.

Due diligence extends beyond quantitative metrics — early funds lack meaningful IRR or multiples — to qualitative signals: reference quality, cultural fit, transparency and adaptability. Ongoing monitoring is more intensive than for established managers, with limited partners often requiring more frequent updates and deeper engagement.

FAQ

Are emerging fund managers riskier than established ones?

Yes, emerging fund managers generally carry higher execution risk, key person risk and operational risk due to limited fund-level history and thinner infrastructure. However, risk varies by team experience and strategy; many deliver strong risk-adjusted returns when backed by proven professionals and disciplined processes.

What track record matters for emerging managers?

Personal and deal-level track record from previous roles carries the most weight for emerging managers. Institutional fund performance is absent or minimal, so investors focus on sourced deals, realized returns, sourcing consistency, and investment judgment demonstrated at prior firms.

Why do LPs allocate capital to first-time funds?

Limited partners commit to first-time funds to capture outperformance potential from nimble strategies, better alignment, and access to less crowded opportunities. Allocations also enhance portfolio diversification across vintages, manager tenures, and market segments where newer entrants often show higher dispersion.

How do fees differ for emerging managers?

Emerging managers typically charge similar 2% management and 20% carried interest structures, but many offer concessions — reduced management fees in early years, hurdles or step-downs — to attract capital allocation. Variations depend on strategy, fund size, and the leverage used in LP negotiations.

Can emerging managers scale successfully?

Many emerging managers do scale successfully into multi-fund platforms when they deliver consistent performance, build institutional credibility, and strengthen operations. Success hinges on maintaining discipline, expanding teams thoughtfully, and preserving the original edge as AUM grows.

Conclusion

Interest in emerging fund managers stems from the combination of elevated but addressable risks, enhanced alignment of interests, access to differentiated fund strategies, and the realistic prospect of meaningful outperformance relative to mature platforms. Limited partners who incorporate rigorous due diligence, prioritize qualitative strengths, and maintain active oversight can benefit from both diversification and alpha generation in private markets. This dynamic explains the continued capital allocation to newer general partners despite structural challenges.