A company constitution defines the internal governance framework of a business. It outlines how decisions are made, how power is distributed among directors and shareholders, and how conflicts are resolved. For any incorporated entity, this document acts as a foundational rulebook that ensures stability and transparency.

Understanding the corporate constitution is essential for founders, boards, and investors. It governs how a company operates beyond what is prescribed by general corporate law, helping prevent disputes and align stakeholder interests.

Company constitution at a glance

A company constitution is a legally binding document that sets out the principles, rights, and procedures guiding how a company is managed. It serves as the highest internal authority for decision-making, complementing national legislation and regulatory standards.

In simple terms, the constitution of the firm defines the relationship between shareholders, directors, and officers. It covers voting rights, director appointments, dividend policies, and procedures for altering share capital. Without this framework, key governance issues would remain undefined or be left to default statutory rules.

While every jurisdiction has its own terminology and format, the goal remains consistent: to establish clarity, accountability, and predictability within the organization.

Core components you’ll typically see

Though the exact structure varies by country and company type, most constitutions include several essential sections.

1. Company objects and powers. This section outlines the business purpose and scope of operations. It defines what activities the company can undertake and sets boundaries that protect shareholders from unauthorized decisions.

2. Share structure and rights. Here, the constitution details types of shares, voting privileges, dividend entitlements, and transfer restrictions. It ensures that ownership and control are clearly understood by all parties.

3. Board composition and authority. This part describes how directors are appointed, removed, and remunerated. It also specifies the limits of their powers and how board meetings are conducted.

4. Meetings and resolutions. Rules for convening annual or extraordinary meetings are outlined here, including notice periods, quorum requirements, and voting procedures.

5. Dividend policy and capital maintenance. The constitution sets guidelines for profit distribution and capital management to maintain solvency and comply with financial laws.

6. Dispute resolution and amendment procedures. It defines how disagreements are settled—whether through arbitration, mediation, or court—and how the constitution itself can be updated.

Together, these components provide a governance framework that minimizes ambiguity and ensures legal compliance across all corporate actions.

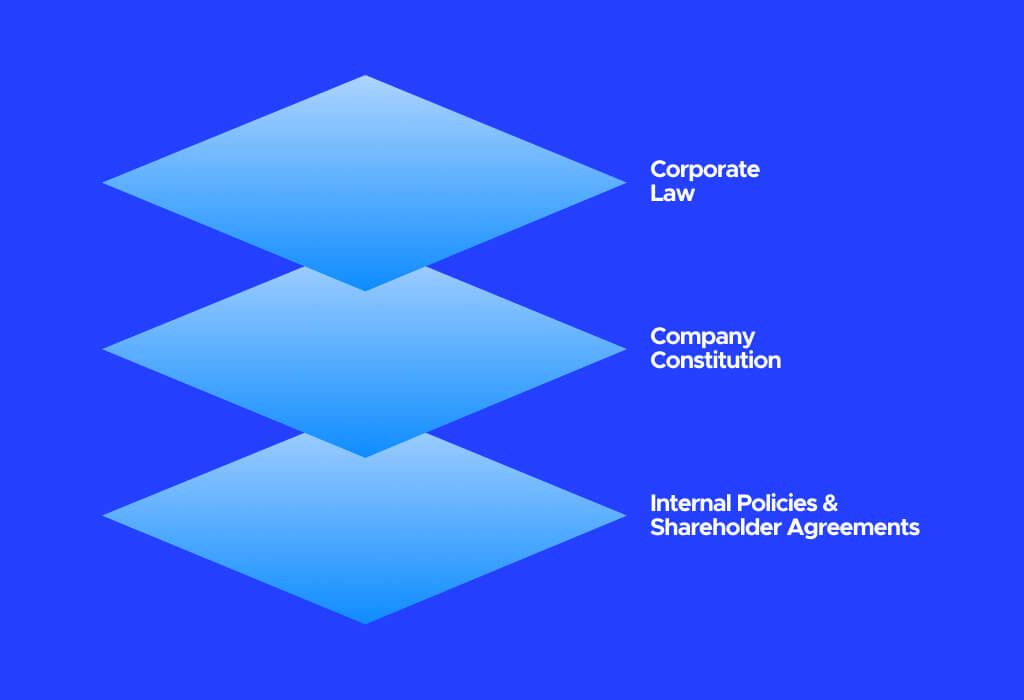

Where the constitution sits in the legal hierarchy

The company constitution operates alongside corporate and statutory law, but it does not override it. Instead, it functions as a contract between the company, its directors, and shareholders, filling in the operational details that legislation leaves open.

In most jurisdictions, the constitution ranks below national corporate law but above internal policies or shareholder agreements. For instance, if a clause in the constitution conflicts with mandatory statutory provisions, the law prevails. However, when statutes allow flexibility, the Constitution provides the binding rules.

This hierarchical balance ensures consistency:

Corporate law defines the baseline obligations.

The constitution customizes governance and decision-making.

Board resolutions and internal policies handle day-to-day execution.

Understanding where the corporate constitution fits legally helps founders design governance frameworks that are enforceable and aligned with the broader legal environment.

Practical benefits for founders, boards, and investors

A well-drafted constitution is not a mere formality — it provides tangible advantages for all key stakeholders.

For founders, it secures clarity of control and prevents misunderstandings as new investors join. By defining director powers and share classes early, founders can preserve strategic influence without discouraging capital inflows.

For boards, the constitution creates a clear decision-making framework. Defined procedures for meetings, voting, and conflict management protect directors from liability and promote efficient governance.

For investors, it provides transparency and predictability. Investors can review the constitution to understand how profits are distributed, what veto rights exist, and how key corporate changes will be handled.

In essence, the company constitution's meaning extends beyond compliance — it supports trust, stability, and professional management practices that attract long-term capital.

Risks and blind spots if you ignore it

Neglecting a company constitution or relying solely on default legal provisions exposes a business to serious governance risks. Without a clear document, the relationship between shareholders and directors becomes ambiguous, leading to potential disputes and delays in decision-making.

Common blind spots include:

Unclear voting rights, causing deadlocks during shareholder meetings;

Undefined director powers, which can result in unauthorized or contested actions;

Missing dispute-resolution clauses, forcing costly litigation instead of mediation;

No capital or dividend policy, creating tension over profit distribution.

For growing firms, these issues can block funding rounds or deter investors who prioritize transparency. A missing or outdated constitution may also conflict with evolving legislation, leaving the company exposed to regulatory breaches.

Establishing and maintaining a well-drafted corporate constitution minimizes legal uncertainty, protects minority shareholders, and supports investor confidence — all critical for long-term sustainability.

Company constitution example

To better understand the structure, consider a simplified company constitution example. While real documents vary in length and complexity, most follow a similar outline that includes key operational and governance rules.

Sample structure:

Preliminary information — company name, registered address, and legal form.

Objects and powers — scope of activities and business objectives.

Share capital — total capital, share types, rights, and transfer rules.

Meetings — procedures for general meetings, voting thresholds, and quorum.

Board of directors — appointment, duties, compensation, and removal.

Dividends and accounts — distribution policies and financial reporting.

Amendments — rules for modifying the constitution or issuing new shares.

Dispute resolution — arbitration or mediation clauses.

This corporate constitution structure provides transparency to all stakeholders and establishes predictable governance mechanisms from day one. Businesses often adapt these sections with the guidance of legal counsel to fit their specific jurisdiction and industry context.

Implementation checklist

Drafting a constitution is only the first step. For it to be effective, the company must implement and maintain it as a living governance tool.

Implementation steps:

Engage qualified legal advisors to ensure compliance with local laws and regulations.

Align the constitution with shareholder agreements and board charters to ensure consistency.

Obtain formal approval from all shareholders at the time of incorporation.

Store a signed copy in the company’s registered office and digital data room.

Review and update the document after major funding rounds or changes in ownership.

Communicate key provisions to directors and officers to ensure operational awareness and understanding.

Following this checklist helps integrate the company constitution into daily management, making it an active reference for decision-making rather than a forgotten formality.