It's rare for a large corporation to operate as a single, monolithic entity. Instead, most are complex webs of parent companies, subsidiaries, and related legal entities across different functions and geographies. This structure enables specialization and efficiency but also creates a significant volume of internal business activity. These activities, known as intercompany transactions, represent the flow of value between different parts of the same corporate group. While they occur internally, their impact on financial reporting, tax liability, and overall operational health is profound, demanding meticulous management and a robust understanding of complex accounting principles.

What Are Intercompany Transactions?

So, what is an intercompany transaction? It is a business exchange or transfer of resources, services, or obligations between two or more entities in the same consolidated group. In simpler terms, it's a transaction that happens within the corporate family—for example, between a parent company and its subsidiary, or between two sister subsidiaries. From the perspective of each entity's legal records, these events are recorded just like any external transaction, creating revenue and expense for the other.

However, from the viewpoint of the consolidated financial statements—which present the entire group as a single economic entity—these transactions are internal movements of assets. The group cannot generate profit or create assets by simply dealing with itself. Therefore, a core principle of intercompany accounting is the elimination of these transactions during the consolidation process to prevent the artificial inflation of revenue and assets and to provide a true and fair view of the group's financial position to external stakeholders like investors and creditors.

Types of Intercompany Transactions

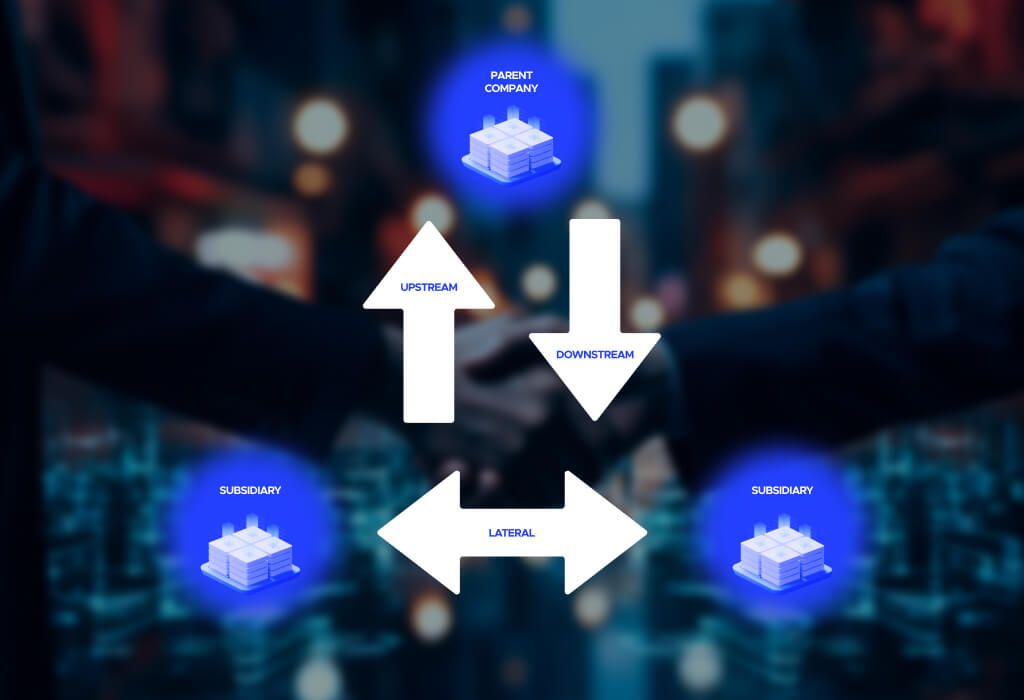

These internal dealings are diverse, reflecting the full spectrum of external business activities. They can be broadly categorized based on the direction of the transaction and the nature of what is being exchanged.

Downstream Transactions flow from a parent company to one of its subsidiaries. Common examples include capital injections, loans provided by the parent, or the sale of assets from the parent to the subsidiary.

Upstream Transactions: These move in the opposite direction, from a subsidiary to its parent company. This often includes dividends, loan repayments, or royalty payments from the subsidiary for the use of the parent company's brand or technology.

Lateral or Sidestream Transactions: This category covers all exchanges between two subsidiaries under the common control of the same parent company. These are often the most frequent type and are critical to the operational supply chain.

These flows can involve various resources, including the intercompany sales of physical goods, centralized services (like IT, HR, or legal support), intellectual property licensing, and financing arrangements.

Examples of Intercompany Transactions

To better understand an intercompany transaction, consider a hypothetical multinational corporation, Global Products Inc., which has two subsidiaries: "Innovate Manufacturing Ltd." and "Retail Solutions LLC."

Sale of Goods: Innovate Manufacturing Ltd. produces electronic components and sells them to Retail Solutions LLC, which assembles them into a final product to sell to external customers. This internal sale is a classic example of lateral intercompany sales.

Provision of Services: Global Products Inc. (the parent) has a centralized finance team that provides accounting and treasury services for both subsidiaries. Each subsidiary is charged a "management fee" for this support. It is a downstream transaction for services.

Financing: Retail Solutions LLC needs funding to expand its operations. Instead of seeking an external bank loan, it borrows $1 million directly from Global Products Inc. This loan and its subsequent interest payments are an intercompany financing transaction.

Intellectual Property: Innovate Manufacturing Ltd. uses patented technology owned by its parent company, Global Products Inc. In return, it pays a quarterly royalty fee to the parent company. This is an upstream transaction involving intangible assets.

How are Intercompany Transactions Typically Managed?

Effective management is crucial to ensure financial accuracy, regulatory compliance, and operational efficiency. The process involves a multi-step workflow handled primarily by the finance and accounting departments.

Recognizing Intercompany Dealing

The first step is simply identifying that a transaction is "intercompany." It requires maintaining a clear and updated chart of all legal entities within the group. In modern ERP systems, each entity is tagged, and specific intercompany accounts are used to flag these transactions automatically at the point of entry.

Recording in the Books

Each entity involved in the transaction must record its side of the event in its general ledger. For instance, in an intercompany sale, the selling entity records revenue and a receivable, while the buying entity records an expense (or inventory) and a payable. These entries must be perfectly mirrored.

Consolidation and Elimination

During the month-end or year-end closing process, the parent company's accounting team consolidates the financials of all subsidiaries. All intercompany revenues, expenses, receivables, and payables are eliminated at this stage. For example, the revenue recorded by the seller and the expense recorded by the buyer cancel each other out, ensuring that only transactions with external parties are reflected in the group's income statement.

Establishing Transfer Prices

A price must be set for all intercompany transfers of goods and services, known as transfer pricing. For tax and legal purposes, this price must adhere to the "arm's length principle," meaning it should be the same as if the transaction had occurred between two unrelated, independent parties. This principle prevents companies from manipulating prices to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions.

Maintaining Compliance Records

Rigorous documentation is non-negotiable. Every intercompany transaction should be supported by formal agreements, invoices, and clear records detailing the basis for the transfer price. This documentation serves as crucial evidence for auditors and tax authorities.

Cross-Border Tax Considerations

When transactions cross international borders, they become significantly more complex. Companies must navigate varying corporate tax rates, withholding taxes on dividends and royalties, customs duties, and differing transfer pricing regulations in each country.

Managing Regulatory and Financial Risk

Poor management of these transactions can lead to severe consequences, including misstated financial reports, hefty tax penalties, legal disputes, and operational bottlenecks. A dedicated focus on risk management is essential.

Regulatory and Audit Considerations

Intercompany accounting is under intense scrutiny from internal and external auditors and global tax authorities. Auditors ensure that transactions are correctly recorded and eliminated during consolidation to prevent material misstatements in financial reports. They will meticulously review intercompany agreements and transfer pricing documentation.

Tax authorities, such as the IRS in the United States, are primarily concerned with transfer pricing. They actively audit multinational corporations to ensure the arm's length principle is being applied correctly, preventing tax avoidance strategies like base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). Compliance with standards set by organizations like the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) is critical.

Different Technologies to Streamline IC Transactions

Given the complexity and volume of these dealings, manual management using spreadsheets is prone to error and highly inefficient. Modern organizations leverage technology to automate and control the process.

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems: Major ERP platforms like SAP, Oracle NetSuite, and Microsoft Dynamics have built-in intercompany modules. These systems can automate transaction posting, currency conversions, and the reconciliation process, ensuring that the books of both entities remain in balance.

Specialized Financial Close Software: Dedicated financial close and consolidation tools are designed to handle complex accounting challenges like intercompany eliminations. They provide automated reconciliation, task management, and a detailed audit trail, significantly accelerating the closing process and improving accuracy.

These technologies provide a single source of truth, reduce manual effort, enhance transparency, and strengthen internal controls over the entire inter-company workflow.

Conclusion – Treat Internal Transactions Like External Ones

The central takeaway for any growing business is to afford intercompany transactions the same level of diligence, documentation, and formal procedure as transactions with external customers and suppliers. While they may feel like internal administrative tasks, their implications for tax compliance, financial accuracy, and regulatory risk are external and significant. Organizations can transform this complex accounting challenge into a streamlined process supporting operational efficiency and robust corporate governance by establishing clear policies, leveraging modern technology, and adhering strictly to the arm's length principle.